by

Robin Gordon

© Copyright Robin Gordon, 2013

Auksford index -- Index to Robin Gordon's works -- Index to Roquana

Book II: Roquana's flight

***

Chapter 7: Tohu

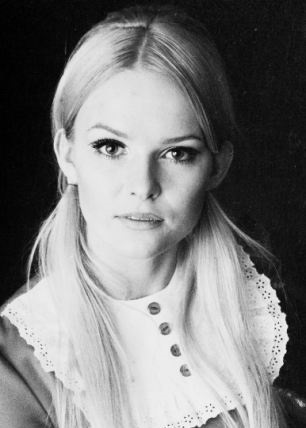

Roquana Smuff (Unknown)

Each of the boys, except Weasel, had contributed one of his sandwiches for Roquana and Tommuz at lunchtime, and Fronk had provided them with some bottles of water and a bag to carry their provisions. Even so they would have to husband their resources and might well be extremely hungry before they reached New Jackrusselham. Fronk had told them to turn left, skirt the agricultural land around the city, and take the first road, which led straight to New Jackrusselham without any of the twists and turns of the roads between Beddleham, Caerbirmingham and Jarwick Hoe. As these detours were made to avoid areas where the Tohu were known to live, he hoped that the straight road to the capital might be free of the savage, bloodthirsty apes, but the sigh he gave as he wished them luck when they got out of his truck clearly indicated that he thought they would likely meet their ends as a feast for the Tohu.

“We’ll have to stay here till dark, then cross the fields to the other road,” said Tommuz, but Roquana reminded him that she had been able to follow animal tunnels through the undergrowth all the way from Savark Court to Beddleham. There could well be similar tunnels around Jarwick Hoe that would bring them to the other road without crossing the fields. Tommuz pushed into the undergrowth, ducking under low branches and flattening brambles and bracken, and it wasn’t long before he found what he sought. The two of them moved, bent double, along the low passageway and soon came to a natural lookout where they could see the city, high on the slope, its farmland spread out beneath it, and the roads to Caerbirmingham and New Jackrusselham meeting below the main gate.

The convoy had come to a halt. The gate was closed. The two Savark carriages were parked across the road, blocking the way, and the truck-drivers and their boys were formed up in a line, being questioned by men in the uniform of Lord Savark’s security guards.

They saw the Convoy Master inspecting the line, saw him speak to the guards, saw Fronk and Korl pulled out of the line, and saw the captain of the guards shouting at them. They couldn’t hear the words, but he was obviously furious, and they saw the labourers in the fields stop their work and turn to stare.

Fronk (George Woodbridge, actor)

Fronk gestured angrily and spat, gestured again then turned to Korl, who nodded vigorously. Jowsif stepped forward and said something, and Stighvin put in a word, while the other boys nodded in agreement as Stighvin pointed back along the road to Caerbirmingham. Weasel, meanwhile was tumbled to the ground, where a couple of lads kept him quiet by sitting on him

Another Savark carriage came hurtling along, this one from New Jackrusselham. The newcomers, also security guards, conferred with the others, asked more questions of Fronk, waved aside the boys who seemed eager to tell them anything they wanted to know, then conferred again. After that the guards dismissed the drivers and their boys, got into their carriages and set off at high speed towards Carbirmingham.

“What was that all about?” Tommuz asked.

“I think,” I said, “that Fronk must have said that he had another two boys but they were so useless that he sacked them and left them in Caerbirmingham. The boys chimed in with lots of corroborative detail to add verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative.”

“My voice says,” said Roquana, and she repeated it word for word.

“You really do have a voice in your head,” said Tommuz. “You’d never had said that stuff about verisimilitude yourself. Perhaps it’s one of the gods come to help us, the Maiden perhaps, or the Lord Grommet.”

“I don’t know what it is,” said Roquana, but I just hope it’s a good voice.”

Dr Sulamun Tadler, Inquisitor (Derek Jacobi)

They set off again along the animal track. Three days’ walking someone had estimated. That might have been so if they had been able to walk openly along the road, but with Savark carriages on the lookout for them, and helicopters scanning the area from on high, they had to stay under cover and the going was far from easy. The tracks seemed to be in constant use, but here and there branches of briars had grown across, in places they had to crawl underneath dense bushes, and at times they had to cross streams. When they came to larger rivers the tracks led them back to the road and they had to hurry over the bridge and search for the hidden entrances.

Rain made them wet and miserable even if they were sheltered from the worst of a storm by the trees, for after the rain was over the wet foliage hung low and showered them with a swoosh of water whenever they pushed it aside. Unidentified insects had bitten both of them before they had gone very far and they had itchy red spots on their hands and round their ankles where the creatures had got in to bite between trouser and sock. Once, after they had crossed a river and were looking for the entrance to the next stretch of tunnel, Roquana brushed her hand against an inoffensive-looking plant and cried out in pain as it stung her. They looked in horror of the reddened skin and the blebs forming on it, both frightened that the poison might prove fatal.

“If I die ...” began Roquana.

“... I’ll find the same plant and let it kill me,” said Tommuz. “We’ll be together again.”

“No,” said Roquana. “If I die you must go on. You must find some way to let the government know what goes on at Savark Court.”

“All right,” said Tommuz, “and then I’ll kill myself to be with you.”

By then, however the pain of the sting was lessening, and in a little while it became clear that the plant’s poison was not going to kill Roquana, and so they continued their journey.

Eventually the track led them away from the road and deeper into the forest. The trees were tall here and their branches closed out much of the sunlight. The undergrowth was sparse and the going much easier – the only difficulty was that, now that they had come out of the enclosed tunnel-like track, it was no longer clear which way they had to go. They could wander randomly among the trees, perhaps going in circles, as people who are lost are said to do, until finally, starved and exhausted, they lay down to die.

“That won’t happen,” said Tommuz, “if we keep close to the thick undergrowth there. It grows like that along the side of the road because there’s more light. If we keep close to that tangle of bushes we’ll be close to the road, and we’ll come to New Jackrusselham.”

“What do you say, Voice?” said Roquana.

“It’s a good idea,” I said. “Better than wandering among the trees.” So she agreed with Tommuz and they set off again.

It was much easier now. They could walk upright, next to each other, and talk as they went. The weather was fine, but Roquana grew more and more uneasy. She was sure that someone or something was following them through the woods. She hadn’t seen anything, nor had she exactly heard anything that she could identify as the sound of pursuit, but still, she felt that they were not alone. Tommuz found a stout branch that had fallen from one of the trees. He broke off the thin side-branches and armed himself with the long straight bough. Through the trees they heard some heavy animal, and Tommuz grasped his home-made weapon ready to defend Roquana, but the sounds moved away.

Roquana was still uneasy. She was still sure that something was creeping after them through the trees, but Tommuz told her not to be afraid.

Then they saw a beast. It was big. It was black or dark brown and covered in bristly hair. It was ugly – and it had tusks.

“Get behind the tree!” said Tommuz.

Roquana quickly hid behind the nearest tree, but she trod on a twig. It snapped and the creature looked up.

“Get away as soon as you can,” whispered Tommuz, gripping his stick.

The animal looked at him, hesitated, then charged. Tommuz crouched and held the branch in front of him. I saw that he didn’t have a chance. The enraged beast would rip him apart with its tusks, but I could do nothing.

The wild beast

It was almost on him when something struck it – a spear, then another. The animal slewed towards its attackers, and a shaggy ape-like creature darted out from the trees and thrust another spear deep into the wounded beast.

It collapsed, and several more apes appeared. They turned towards Tommuz, who brandished his stick, determined to fight off any attack – but it seemed to me that the noises they made weren’t just animal grunts. I listened, then I said to Roquana, “Tell him to drop the stick. They are talking. They have language. They’re intelligent. Friends.”

“Tommuz,” she called. “Drop the stick. They’re friends. My voice says.”

Tommuz hesitated, then he put down the stick. One of the apes picked it up and went over to the beast. The apes tied its legs together over the pole and hoisted it onto their shoulders.

One turned to Tommuz and Roquana.

“Chumba!” he said. “Chumba gif utzi. Choo itzi vortsha gif utzi. Chumba! Chumba!”

They hesitated. The Toho flung back his hood and they realised that he wasn’t a hairy ape but a bearded young man wearing garments made out of animal pelts.

“Chumba!” he said again, then, pointing at the dead animal slung on the pole, he said again: “Tshoo itzi vortsha gif utzi. Chumba.”

“I think, said Tommuz quietly, “he means if we don’t come quietly we’ll end up dead like that thing. We’d better go.”

The Toho obviously approved.

“Chetzi, chetzi,” he said, nodding his head. “Chumba!”

“Out of the frying pan ...” murmured Tommuz.

The Tohu led them through the trees and eventually into an area where the forest grew through odd rough ridges in the ground. They came to a hillock, pulled aside a tangle of vegetation and revealed a door. Steps led down into an underground cavern, though it was rectangular, not natural but made by the Tohu. A stone passage led to another door, and beyond it was a large hall with several doors leading off it. The Tohu stopped there and pulled off their shaggy animal skins revealing inner clothing made out of wool and leather. The dead animal was carried off, and the Toho who had spoken before turned to them and said something that sounded like “Gaytsi chiyaha,” and gestured towards a row of chairs. They sat down to wait, guarded by a couple of the Tohu, while the leader went through another door, obviously to report to some more important Toho that two humans had been taken.

After a while he returned with some other Tohu, older males it seemed, more solid in build, slower in movement, and with grey beards and grey or absent hair. They conferred together for a few moments, then one came forward.

“Welcome,” he said, smiling. “Welcome to the underground city of the people you call Tohu. I am Vayhal, one of your own people, though when I lived among you I was called Moiku. Like you I fled from the evils of the rulers of Sunday and found my way to the wild people of the woods. Do not be afraid. No-one will harm you here.”

Vayhal (George Clooney, actor)

“We thought,” said Tommuz, they would kill us if we didn’t go with them.”

“I wonder what gave you that idea.”

“They pointed at the dead animal and said Choo arsi vorshti giv ushti.”

“Choo itzi vortsha gif utzi?”

“Yes.”

The man chuckled. “And they pointed to the pig? It means You eat pork with us. They were inviting you to dinner, and you will eat pork, though not that particular wild boar today – it will have to be butchered and hung for a while to develop its flavour – but you must be both tired and hungry. Come with me and have something to eat, then you can sleep, and tomorrow you can tell us your story.

The next day they were led by Vayhal into a beautifully panelled room, where five elders sat on ornately carved chairs, almost thrones along one side of a polished table, while Roquana and Tommuz sat on smaller, plainer chairs opposite, and Vayhal took his place at the end of the table.

“These gentlemen,” he said, “are the elders of this tribe of woodland people. They would like to hear your story and why you have chosen to flee into the wild forests. Perhaps, Tommuz, you could begin. Speak slowly and leave me time between your sentences to translate.”

Tommuz (Jonathan Bailey, actor)

Tommuz began.

“I lived with my widowed mother in Gollerlley,” he said, “until I was recruited to work for Lord Savark at Savark Court. It was there that I met Roquana, who, in spite of her male clothes, is a girl, not a boy.”

He told how he had been stripped of his trousers by his fellow footmen and taken refuge in Roquana’s room, and how Roquana had later been told that this was standard practice intended to identify girls who could lie well and keep secrets, though in Roquana’s case there was no secret to keep. He told how they had been thrown together by the Housekeeper and Butler, who probably believed they were indulging in sexual intercourse in the gardens. He told how they had befriended old Wullum and his apprentice Moiku, and how Moiku and the other boys had been lured by Mrs Bonpoint, and Moiku chosen, castrated and made into a kitchen maid. He told how Lord Savark had held a party for the so-called great and good, members of the governing classes and the League of Purity, how he himself had been employed on errands to keep him away from Roquana, how she had seen sexual misbehaviour which would have destroyed the reputation of Savark’s circle, including sexual assaults on young children, how she had been attacked, and how, on appealing to Lord Savark for help, she had been subjected to an attempt at rape.

The elders nodded sagely as Vayhal translated Tommuz’s account, and on hearing of Roquana’s molestation, put through him the question how she escaped.

“I kneed him in the balls,” she said, “and he collapsed.”

When Vayhal translated this the elders chuckled in approval and smiled at Roquana.

Tommuz then described how they had fled to Beddleham, and how Roquana had been frightened when a Tohu had seized her and carried her off, grunting “Got her! Got her!” before dropping her in a stream as the hounds drew near.

Vayhal translated and the elders chuckled again. Then Vayhal explained.

“The young hunter who picked you up was helping you escape. What he said wasn’t got her but góthekha, which in their language means water. He wanted you to walk along the stream, in the water, so that the hounds would lose your scent.”

After that Tommuz described what had happened in Beddleham and their journey to Jarwick Hoe, and how Fronk and the truckers’ boys had helped them. The elders expressed satisfaction, asked Vayhal to tell Roquana and Tommuz the history of the Tohu, and withdrew.

This, I thought, ought to be interesting. The Tohu, or wild people of the woods, as they preferred to call themselves, were obviously human. Were they renegade settlers who had fled into the forests to be free of the strict morality imposed by the government of Sunday, and, if so, was their language a code they had devised so that government representatives could never understand them? Or, on the other hand, was Sunday a planet that had been settled before? Had it been abandoned leaving some of the colonists behind to live out their lives in the jungles, or had it lost contact with the Commonwealth, abandoned its civilisation, and declined into a primitive hunter-gatherer society? Did the Sunday Development Corporation know that the Tohu were human or did the ruling class believe, as they told the rest of us, that the denizens of the forests were really carnivorous apes?

“The Tohu,” said Vayhal, “are, as you have doubtless realised, human beings. They are the aboriginal inhabitants of this planet, for this world, which the government has called Sunday, is, in fact, the long-lost original home of mankind. This is Earth.

“When the Ommarigu and the Choinezzu between them finally destroyed the environment of the whole planet, and the King led the Great Exodus, obviously not all the people on Earth, not even everyone in the King’s own country, could fit into the spacecraft. Those that were left behind were forced to eke out a miserable existence, largely underground, wearing protective clothing whenever they ventured out of their burrows. Many millions died, but small colonies survived here and there, including our groups here in Unglind.

“When the Sunday Development Corporation rediscovered this world, they quickly realised that there were tribes of the original inhabitants still here, but knowing that Commonwealth laws insist that any intelligent species discovered on any planet should be allowed to live in undisputed possession of their world, or if there was room for human settlement and the indigenous population agreed to it, then they should have the full rights of Commonwealth citizenship, they decided to conceal their discovery.

“Development Corporation surveyors sought out areas away from the main concentrations of the original inhabitants and away from the ruins of our ancient cities, for it would not take a trained archaeologist to recognise the remains of urban developments, many of them extending over large areas.

“When the Development Corporation did choose to mention the original inhabitants, they described them as vicious, carnivorous apes that fed on human beings, as you know. This helped to keep the settlers concentrated in areas where the Corporation could keep its eye on them, and justified killing the Tohu whenever they came near to the new settlements.”

Roquana and Tommuz were shocked, as was I, the unseen observer.

“Surely,” said Roquana, the Senate cannot be aware of all this, or the Holy Synod?”

“We do not know just how far the knowledge is shared among the establishment,” said Vayhal. “Lord Savark and his associates in the Sunday Development Corporation are all fully aware of it and orchestrating the genocide and the terrorising of the colonists. It may well be that the Inquisition knows of it, for they seem to know everything about everyone. Some members of the Senate undoubtedly know, and very possibly some members of the Holy Synod. From what we have been able to find out about her, it would seem that the President is innocent of any complicity.”

“Then we must tell her,” said Roquana. “I’m sure she will try to put things right as soon as she knows what has happened.”

“How can any of us approach the President?” said Vayhal. “Those few of us who fled from the colonies are known to and wanted by the authorities. We have taught Unglush to a number of the wild people, and several of our young men have even sacrificed their beards in order to enter New Jackrusselham and walk about undetected to observe and listen, but even the most proficient of them speak with native accents and could never approach any official.”

“We’ll go,” said Roquana. “We were making for New Jackrusselham anyway. We wanted to lose ourselves in the crowds there, but perhaps we can find a way to contact the President.”

“I am very unwilling to let you take such an appalling risk,” said Vayhal. “Lord Savark’s men will be hunting for you, and, though they think you are at Jarwick Hoe or Caerbirmingham, they will still be on the alert for you in New Jackrusselham.”

“It really is our only chance,” said Roquana. “Surely the President will listen”

I used to like Old Bonita Bananas when she was on television,” said Vayhal, “ and, as I said, I’m sure she would never have agreed to genocide. There was always something so wonderfully innocent about her.

It’s OLD Bonita Bananas,

Bonita Bananas, olay!”

he sang. “But if what you tell me about Jamal Fittlutt is true, how can we trust anyone?”

“I always found Jamal Fittlutt a creepy sort of person,” said Tommuz. “He came to Gollerley to do a show there, and I went with my mother, and we both thought he was quite peculiar, but when Old Bonita Bananas came it was quite different. She was such a jolly sort of person you couldn’t help liking her. I think it’s worth a try.”

Old Bonita Bananas

President of Sunday

(Miranda Hart, actress)

“Well,” said Vayhal, “I’ll put it to the Elders and see what they say. I’m afraid you’ll have to shave, Tommuz.”

Tommuz stroked his stubble. “I’ll be glad to get rid of this,” he said. “I must look frightful.”

Vahal laughed. “I was forgetting,” he said. “You’re used to being clean-shaven. Shaving is a real sacrifice for our men. They feel undignified, as if they’d gone back to being prepubescent boys. They feel about losing their beards much as you would feel if you were forced to go round without your trousers – but they do it: for the good of the community. Anyway, I’ll put your proposal to the Elders and we’ll see what they say.

What the Elders said was yes. They recognised the danger, but, if the original human inhabitants were not to be totally exterminated by the newcomers, the truth about the Sunday Development Corporation had to be revealed. Getting to the new President might be the only possible chance.

Tommuz shaved, and he and Roquana were given new clothes bought or stolen in the city, and, after a couple more days of rest, they set out, accompanied by half a dozen young men of the Tohu, clean-shaven and dressed as colonists, and by a couple of girls.

They walked rapidly through the forests, for the Tohu knew their way around every inch of their territory, camped overnight, when the young men took turns to keep watch, and then camped again a short distance from the city. The next morning they rose at dawn and were ready to join the agricultural workers in the fields.

At the edge of the forest trees were being felled to extend the farmland, and one of the Tohu explained that as the farmland encroached on the forest, so the city expanded into the fields, the newly felled trees being used for stockades around the new suburbs.

They slipped out of the forest and watched the felling of trees and the dragging out of the stumps, looking like farm-labourers taking a break, then set off towards the city gates, seeing as they approached them a convoy of trucks and buses, which, the Tohu said, were bringing cargo and new settlers from the space-port, then, about mid-morning, they passed through the gate and entered New Jackrusselham.

See Copyright and Concessions for permitted uses.

***

Roquana:

Index.

Chapter 6: The road to Jarwick Hoe

Chapter 8: City of the Apostle

***

Auksford index. -- Index to Robin Gordon's works.

Send an e-mail to Robin Gordon.