Auksford

2013

©

Copyright Robin Gordon, 2013

Auksford

index -- Index

to Robin

Gordon's works

--

Index

to Roquana

Book

I: Savark Court

***

Chapter 1: I meet Roquana

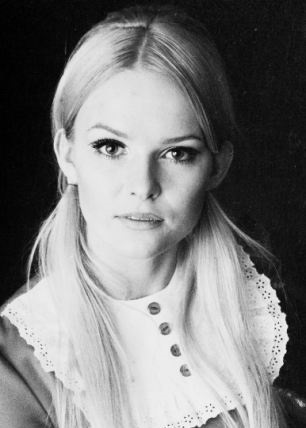

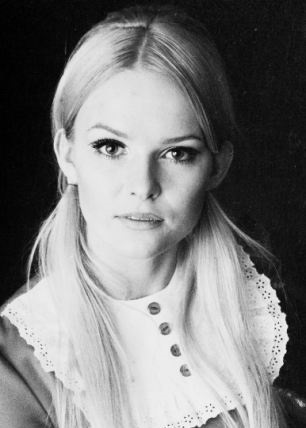

Roquana Smuff

The common people cannot be said to have ever properly

appreciated the Holy Inquisition. Snoopers they call us, and

some

of the powers they attribute to us are beyond all reason. I

have

heard it said that every inhabitant of Sunday is assigned a personal

Inquisitor from the moment of his or her birth to remain with that

person until the moment of his or her death. Can you imagine

the

number of Inquisitors we should have to have if that were

true?

Or the complications that would ensue if an Inquisitor died before his

assignee? I remember some old woman told me this piece of

nonsense when I was ten or twelve. “Don’t

ever do

anything naughty,” she said, “or you’ll

make your

Guardian Inquisitor angry and he’ll tell the

authorities.”

“If

I have a Guardian Inquisitor,” I said,

“and he stays with me all the days of my life …

then he

must be the same age as me, and boys don’t split on each

other,

so I don’t have to worry.” The old woman

prophesied

that I’d come to a bad end, but the other adults laughed, and

it’s my belief that’s when I was picked to join the

team.

The Office of the Holy

Inquisition is quite a

select band. There are not all that many of us, so of course

we

cannot watch every man woman and child on the planet for twenty-four

hours a day, three hundred and sixty-five days a year. That

would

be absurd. I had always believed that the Inquisition

computer

allocated subjects for supervision entirely at random, and that it had

at its disposal the identities of the whole population without

exception. Then I discovered my mistake.

Dr Sulamun Tadler, Inquisitor (Derek Jacobi)

My story begins when I was allocated a girl of

19 called Roquana Smuff.

I had first, of course, to make contact

with the

subject. We Inquisitors cannot, as some people fondly

imagine,

tune in to the wavelengths of anyone on the planet. It is

necessary to arrange an initial meeting in which we come into the

physical presence of our subject, who, naturally, remains unaware that

anything unusual has occurred.

Roquana was on her way home when an

elderly man

stumbled in front of her, fell on the ground, and scattered his

shopping across the pavement. The helpless old man trick was

not

one I would have dared to play in our capital city, New Jackrusselham,

where swarms of hoypyu are always on the lookout for victims to

rob. Usually they prey on rival gangs, but I have seen the

occasional elderly citizen robbed and stripped entirely naked.

In Beddleham it was pretty

safe. A few of the

passers-by laughed derisively, and a hoypyu boy snatched up one of the

old man’s purchases and made off with it. Roquana,

however,

stooped, took the old codger by the hand, and helped him to his

feet. I, for it was I, in disguise, held her hand for

slightly

longer than necessary, and stared into her eyes while I stammered my

thanks.

“Well, you’ll

certainly know me

again,” she laughed.

“I will indeed,” I

quavered as she

stooped to pick up my possessions and stow them in my shopping bag.

Dr Tadler

disguised as a confused old man

Dr Tadler

disguised as a confused old man

(Derek Jacobi)

She went on her way, and I returned to

the Palace of

the Holy Inquisition in New Jackrusselham. There, following

standard practice, I drank a potion brewed from certain herbs that are

grown in the palace gardens, lay down on my bed, connected my body to

the life-support system, and concentrated my mind on locating Roquana

and entering her mind.

She, of course, was totally unaware of

the unseen

eyes that saw whatever she did, the unheard ears that heard all that

she heard and all that she said, and the untraceable mind that followed

her every thought and knew her every impulse.

Roquana was a nice girl, a thoroughly

nice

girl. She lived with her widowed mother, was helpful about

the

house and was an efficient assistant in a nearby shop. Apart

from

her unfailing niceness there was nothing out of the ordinary about her,

and I was about to withdraw from her mind and give her a clean report,

when something unusual happened that piqued my curiosity.

As I believe I have already said the

Inquisitorial

computer is supposed to select and allocate subjects entirely at

random, including the whole population of Sunday from the oldest

inhabitant to the youngest, and from the poorest beggar to the

President herself, yet neither I nor any of my closest colleagues had

ever dealt with anyone from the upper echelons of society: the Lords

and Ladies, the members of the High Council, the Senate or the Holy

Synod, or even such subordinate bodies as the Monopolies Control

Commission. I had begun to suspect, though I knew it was

unwise

to voice such suspicions, that the random process was far less random

than I had been led to believe. Only to my wife and my

closest

colleague, Ulixondir Drow, would I ever have voiced such suspicions,

and even then we referred to treat it as a joke and to suppose that the

Grand Inquisitor reserved for himself and the Eminences, the senior

Inquisitors, the Monsignors, any investigation into members of the

establishment.

That was why my curiosity was aroused

when Roquana

and her mother received an unexpected visit from the Private Secretary

and the Chatelaine of no less a personage than Lord Savark, the

Chairman of the Monopolies Control Commission and one of the richest

men on the planet.

I decided not to withdraw at once,

justifying my

decision on the grounds that I had seen Roquana interacting only with

her social equals and inferiors in one of the poorer towns, and that to

secure a complete characterisation of my subject, I should see how she

behaved in the presence of the rich and powerful. It was

always

possible that even the nicest person might be tempted into some form of

dishonesty when confronted with the conspicuous consumption of the

wealthy, (even if it were only the snaffling of the odd biscuit from a

plate), or that they might indulge in obsequious flattery to secure

some minor advantage. If I were to be entirely honest, I have

to

admit that I also wanted to see how the great and the good behaved

towards the small and insignificant when they believed themselves

unobserved.

It was Secretary Gulls who began the

conversation. He and the Chatelaine had drawn up outside in

one

of those ridiculous carriages affected by the rich: electric, of

course, like any other vehicle on the roads, but equipped with an

entirely unnecessary array of artificial draught animals, in this case

a pair of dragons with flashing eyes, flapping wings and streams of

sparks issuing from their jaws. The idea was to intimidate

the

common people, to make them jump out of the way and impress them with

the importance of the occupants.

Despite the vulgar flashiness of the

car, which may

well have been the choice of his employer, or even of his

employer’s head stableman, the secretary made a very

favourable

impression on me, as he did on both Roquana and her mother.

Although obviously a man of considerable influence and importance he

had the knack of making the ladies feel that they had his full

attention, the ability to condescend without in the least making his

interlocutors aware of any hint of condescension. He was

indeed

the perfect conversationalist, achieving a combination of friendliness

and attention that could not fail to charm.

Monsignor Gulls

(Unknown)

Monsignor Gulls

(Unknown)

He spoke of his employer, Lord Savark,

the guiding

hand behind the discovery and colonisation of Sunday, the man who had

organised the survey of the planet and picked out safe sites for the

new cities, as far as possible from the main concentrations of the

savage Tohu, (wild bloodthirsty beasts whose greatest delight would be

to feast on human flesh), the architect of their defence, the

civilising influence who had ensured that Sunday would be a morally

irreproachable place, and the founder of the League of Purity that kept

young men and women of the Sunday colonies free of the addictions to

alcohol, drugs and the sexual shenanigans that plagued so many frontier

planets.

He spoke too of his companion, Madame

Yowfrasinny

LaTower, the Chatelaine of Lord Savark’s country manor, the

organiser in charge of the whole household, with oversight over the

butler and his under-butlers and footmen, the housekeeper and her

maids, the cook and the kitchen staff, the head gardener and the

under-gardeners, the head-stableman and his staff of chauffeurs and

engineers who drove and maintained Lord Savark’s fleet of

vehicles. His admiration for Madame LaTower’s

wide-ranging

responsibilities, and the efficiency with which she carried them out,

was boundless.

Madame LaTower,

the chatelaine (Sian Phillips)

Madame LaTower,

the chatelaine (Sian Phillips)

Of himself he said little directly,

beyond the facts

that he was Lord Savark’s secretary and that his name was

Gulls,

though it became obvious as he talked that secretary

was a modest title for a

man who seemed to be nothing less than Lord Savark’s right

hand

man and the organiser of both his social life and his business ventures.

On his entry I had mentally classed him

as Doctor

Gulls, the title of Doctor

being reserved for officials

of a certain standing, including not only medical men but civil

servants, lawyers, and Inquisitors such as myself. As he

talked I

began to think that, despite his obvious modesty, he must be at least a

Monsignor,

for he was

obviously the equal of the Chatelaine, whom he called Madame

LaTower, and possibly of

higher rank.

Now he began to enquire into Mrs

Smuff’s

circumstances.

“For you are not actually

a widow,”

he

said.

“I have to admit that I am

not, Sir,”

she replied. “I have to admit to you that I was

never

married, but I beg you not to think ill of me until you have heard my

tale. I am the daughter of a respectable clergyman, who may

still

be living for all I know, for I left the town where he resides as soon

as I discovered that I was pregnant, so as not to bring shame on an

honest and honourable man of the cloth, though it was not through any

shameless or immoral practice that I conceived my child.

“Her father was a

dentist. I went to him

for a course of treatment, and, as I was a rather nervous girl, afraid

of the drill and other instruments, he gave me an injection of

roquanine.”

“How fortunate,”

interrupted

Gulls. “So instead of enduring

the filling of your tooth,

you found it extremely pleasurable.”

“I did indeed, Sir,”

she said.

“He could have pulled out all my teeth and my fingernails one

after the other, and I would have begged him to carry on. He

filled my tooth, Sir, then his hands began to wander to other parts of

my body. I was like moulding clay in his hands,

Sir. He was

able to do whatever he liked, and that, Sir, is how my daughter was

conceived – and why I called her Roquana,

a name that reminds me

of my shame and, at the same time, reassures me that the fault was not

mine.”

“Why didn’t you

raise a complaint

against

the desecrator of

your virtue?” Gulls

asked.

“You could have had him struck off and

very probably forced to

compensate you.”

“Oh no, Sir,” replied Mrs

Smuff. He was the leading dentist in town, the chairman of

the

local dentistry faculty, and quite a bigwig in the World Dentistry

Association. He wasn’t just a doctor, Sir, he was a

monsignor, and no-one would have believed my word against

his. He

would have accused me of promiscuity and of trying to hide my

wickedness by an unjust accusation against him. My family

would

have been dragged through the courts. It would have killed my

parents. So I left them a note saying I had fallen pregnant

by a

boy who refused to marry me and that I was going away. I

begged

their forgiveness and asked them not to try to find me. As

far as

I know, Sir, they never did try. My father was well-known for

the

severity with which he dealt with girls in a similar situation, so it

would have been impossible for him to forgive his own daughter without

being accused of hypocrisy.”

“I see,” said Gulls,

“and is

Roquana acquainted with

the

story of

her

conception?”

“She is,” replied

Mrs Smuff.

“When she was old enough to understand, I told her

everything.”

“So your name is not really

Smuff?”

“No, Sir, it isn’t,

and I am not

prepared to tell you my real name because of the distress it would

cause to my parents and my brothers and sisters. I called

myself

Mrs Smuff because Smuff is a very common name.”

Mrs Smuff

(Rebecca Front)

Mrs Smuff

(Rebecca Front)

“You realise, of course,

what a very great honour it

will be for

Roquana to enter

the household of

so great a

man as

Lord Savark?”

“I do,

Sir,” said Mrs Smuff

humbly. “I know she’ll be a good girl and

do her best

to give satisfaction.”

“Excellent,” purred

the secretary.

“I think everything is in

order. Lord Savark’s housekeeper, Mrs Broyn, will

pick

Roquana up

tomorrow.

Please have her things packed up and ready to go by two

o’clock.”

With that the secretary and the

chatelaine took

their leave.

“Do I have to go?”

said Roquana.

“I’d much rather stay with you. I

don’t want to

go off and work in Lord Savark’s estate.”

“Of course you have

to,” said Mrs Smuff

sharply – far more sharply than I had ever heard her speak

before. “We can’t not do what they

say.

It’s not an invitation

to work for them, it’s an order.

If you don’t go they’ll make sure your life

isn’t

worth living. Remember Mork Pottle? They sent for

him, and

he didn’t go, and within a couple of months he was

dead. Of

course you have to go. Just try and keep out of sight as much

as

possible. Be as inconspicuous as you can.”

Then they flung their arms around each

other and

wept, which, I must say, rather puzzled me, for this, surely, was a

great opportunity for Roquana to leave behind the poverty into which

she was born and to make her way in the world. Living and

working

at Lord Savark’s manor, and under the supervision of a man

like

Monsignor Gulls must open up to her possibilities of advancement far

superior to any she could find in Beddleham.

The Housekeeper’s carriage was

nowhere near as

flashy as that which had brought Monsignor Gulls and Madame LaTower,

though flashy enough in all conscience, with its pair of winged horses

that snorted, neighed and reared as it approached. Mrs Broyn

herself seemed kindly, and Roquana and her mother parted, tearfully but

with their composure comparatively unimpaired.

Mrs

Broyn, the Housekeeper (Unknown)

As we drove through the narrow streets

of Beddleham

the populace scurried out of our way, often heaving heavy bundles or

barrows aside to make way for the carriage, and saluting it most

humbly, for the people of Sunday, third planet of the system, are

imbued with gratitude to the nobility who discovered and organised the

settlement of this most wonderful of worlds, with its plethora of

different fruits and healing herbs and an atmosphere miraculously

attuned to the needs of its human colonists, and they take every

opportunity to show their respect. Roquana was now leaving

the

world of the common people to work directly for one of the greatest men

on Sunday. She had the honour of entering the service of Lord

Savark, and, though his staff was large, might well be actually spoken

to by the lord himself on occasion. Nevertheless I felt her

sadness at leaving her beloved mother, and her apprehension at moving

into a new social sphere of which she had no experience.

Then we left the city gates, crossed the

fertile

farmland, where labourers were working hard in the fields, and entered

the dark forest. The road led onward through the trees and

Roquana, I could feel, was nervous, as well she might be. Had

we

not been told over and over again, in newspapers, radio and television

broadcasts and the world-wide computer network, that the forests were

the domain of the savage Tohu, carnivorous apes who had already in the

short time we had been on Sunday developed an abiding hatred for humans

and a taste for our flesh. According to report after report,

they

lay in wait in the forest, and if any farm-labourer chanced to stray to

close to the boundary, or, as occasionally happened, took shelter in

the trees to relieve himself, the Tohu would seize him and tear his

living body apart, limb by limb, cramming his flesh into their bloody

mouths, while his fellows, terrified by his screams, would flee towards

the safety of the city.

“Aren’t you afraid

of the Tohu,

Ma’am,” she eventually asked Mrs Broyn.

“Bless you, no,

child,” the Housekeeper

replied. Savage they may be, but they have learned to respect

Lord Savark’s carriages. We always carry a gun, and

in the

early days we’d travel in convoy with a score of armed

men.

Many a Toho has paid for its aggression with its life, and now they

keep well clear of us. You’re quite safe in the

carriage,

and you’ll be quite safe at Savark Court.

There’s not

a Toho would come within a mile of it.”

Please

remember that this story is

copyright.

See

Copyright

and Concessions for permitted

uses.

Roquana:

Index -- Roquana:

Chapter 2: Lord Savark's household

Auksford Index.

-- Index

to Robin Gordon's works

Send

an e-mail to Robin

Gordon